Fourth-year College of Medicine students got a taste of how decision making and priorities change when facing economic hardship through a role-playing event held recently in the Ralph Regula Center. Small groups of students were divided into families, with each member assigned a role and each family assigned a backstory. Every family had the same goals: to meet their fundamental needs – such as paying for food, utilities, and transportation – and to manage unexpected situations and expenses over the course of a month.

Each week (represented by a 15-minute segment, ending with a whistle signal), the family had to deal with stressors like trying to get to work with limited transportation resources, getting kids to and from school or daycare, and visiting businesses that were only open during hours when they were supposed to be at work. University faculty and staff members operated booths around the room, representing the places a family might need to visit: a department of social services, an employer, a grocery store, school, bank, payday advance store, pawn shop and more.

Feeling the struggle

“I felt a lot of moments of desperation,” said student Carl Allamby in a group discussion afterward that was led by Joseph Zarconi, M.D., professor of internal medicine.

It seemed like there was never enough time to get everything done, the students agreed. If they stood in line at the bank to cash a check, only to find that they weren’t allowed to do that without an account, it meant spending more time and money traveling to a cash advance store, where a hefty surcharge was taken out of the check amount.

What would you do?

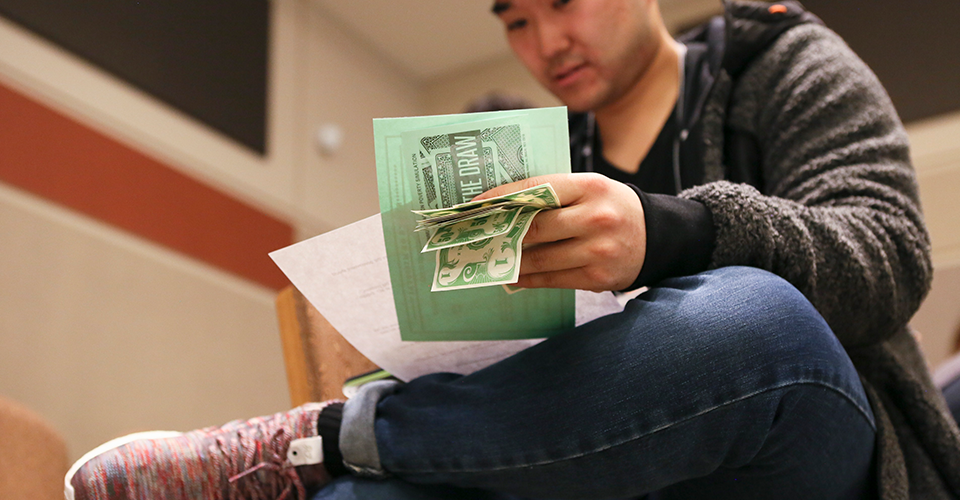

Feeling strapped because they were short on the transportation vouchers they received at the beginning of the simulation, many students rushed to a pawn shop to raise money, not realizing that they could have received help paying bills through a community action agency. Others haggled with neighbors to trade belongings for transportation vouchers. Many had to make difficult decisions that included not picking up needed prescriptions or getting health care because of the costs.

Nick Marshall, who is headed toward a career in pediatrics, said afterward that in playing the role of a child, he found himself saying, ‘No, that’s ok, I don’t have to do that craft,’ at school, because the art supplies cost money that he knew his simulated family didn’t have.

Embedding empathy

The Community Action Poverty Simulation Program was developed by the Missouri Community Action Network. It’s used by a wide variety of institutions and community organizations nationally to build understanding and empathy for people experiencing financial problems among those who help them. Future physicians fall into that category, says Erica Stovsky, M.D., MPH, assistant professor of internal medicine, who led the day’s event with Nichole Ammon, clinical assistant professor of psychiatry.

This year, all fourth-year College of Medicine students participated in the program as part of their Clinical Epilogue and Capstone Course. The goal is to gradually integrate the program into the curriculum for first or second-year students.

As one student summed up afterward, it’s easy to get cynical if someone doesn’t show up for appointments and do what the physician tells them, but just getting to the appointment may be a huge struggle. It may change your point of view if you think about everything the patient may be going through.